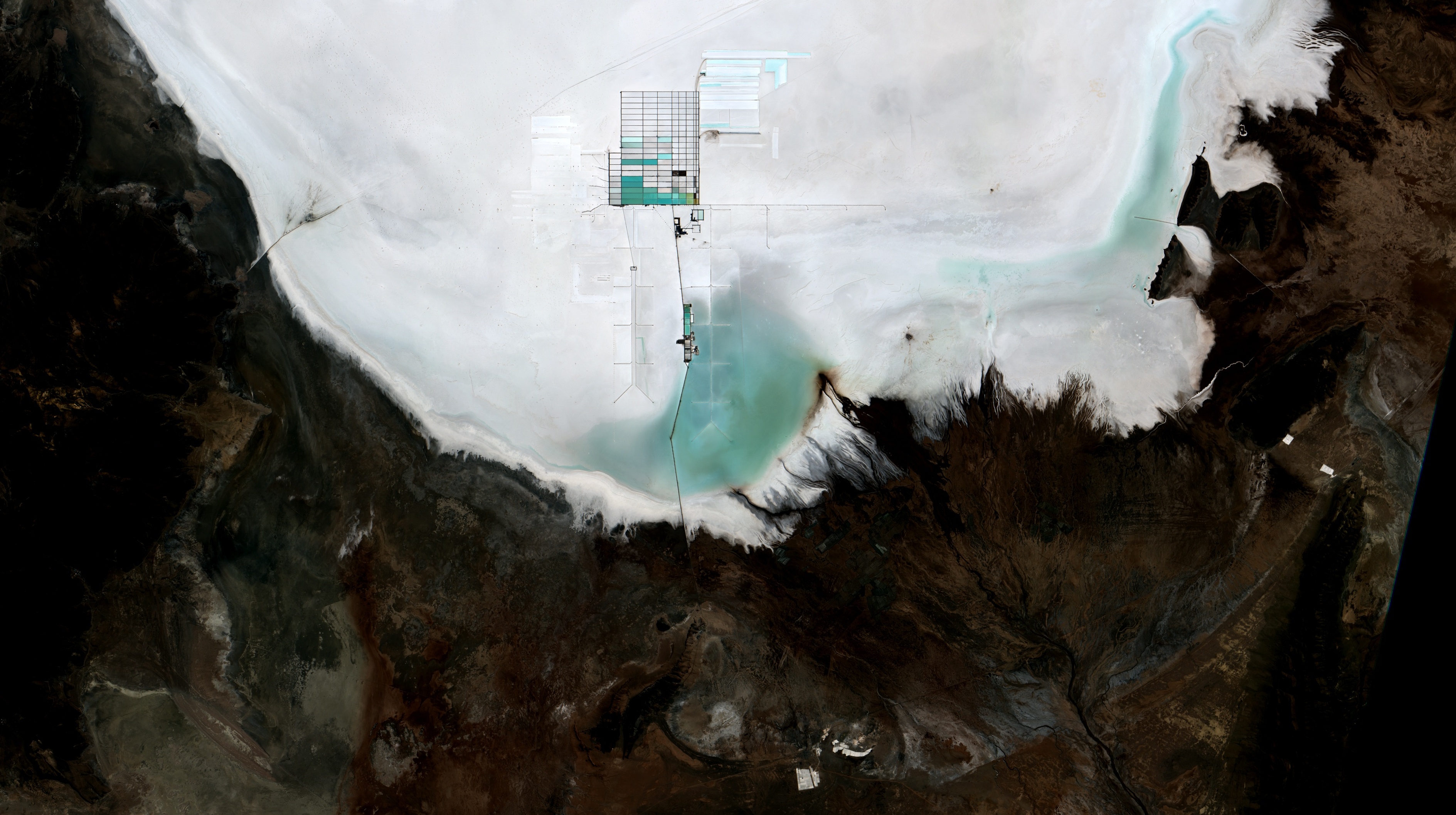

Raw materials (RM) are a crucial part of our everyday lives and the backbone of the economy: Nearly every economic process starts in some form with raw materials. Whereas some of these materials are omnipresent, like oil, others remain outside the broader public’s eye, like niobium or bismuth. But from time to time, and often because of technological developments or scandals connected to their extraction, certain raw materials step into the spotlight. This is evident with lithium and cobalt, crucial components in batteries for electric vehicles (EV), whose importance has surged in recent years. They lead the conversation regarding the rising demand for raw materials for ecological modernization and the heightened concerns among Western nations regarding import dependence. Consequently, they are classified, e.g. by the EU, as Critical Raw Materials (CRMs).

What are CRMs?

The term CRM was introduced in 1939. With the Second World War looming, the US government released the “US Strategic and Critical Materials Stock Piling Act”. In an Amendment to this Act in 1979, the terms CRM and Strategic Raw Material were defined as “materials that would be needed to supply the military, industrial, and essential civilian needs of the United States during a national emergency and are not found or produced in the United States in sufficient quantities to meet such need.”

In Europe, the concept of CRM was only introduced in 2008 amid mounting concerns regarding undistorted access to raw materials, rising prices and supply disruptions. As part of the European Raw Material Initiative the EU Commission started publishing a list of CRMs every three years. Starting in 2011 with just 14 CRMs, this list grew to 20 by 2014, to 27 in 2017, and 30 raw materials in 2020. In its most recent list, 2023, this has been expanded to 34 raw materials.

The classification of criticality in the EU is the result of a complex technical assessment and stakeholder consultation, where the EU screens a wide range of raw materials (for the 2023 report, 87 RM). There are two major categories: Economic Importance and Supply Risk. Economic Importance evaluates substitution indices, the importance of these raw materials for specific sectors, and the economic value of those sectors to which these raw materials are essential. Supply risks are bottlenecks, especially in the extraction and processing stages, and parameters like global supply concentration, EU sourcing concentration, import reliance, trade restrictions, recycling capacities, and national governance criteria.

For the 2023 assessment, 34 raw materials were proposed as CRMs; these range from the heavy and light rare earth elements, to lithium, cobalt, coking coal, helium, magnesium and aluminum.

What makes these 34 raw materials critical?

The technocratic answer is that they all reached a Supply Risk Factor higher than 1 and, at the same time, an Economic Importance Factor higher than 2,8. Or, to put it differently, although each of these raw materials differ in their specific function, geological and chemical characteristics, all of them possess unique characteristics currently vital to the EU economy alongside significant risks in the supply chain. But a clearcut and widely accepted definition which Raw Materials count as critical does not, and cannot, exist, as criticality is a dynamic and ‘fluid’ condition:

Criticality is subjective.

In 2023, the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) reviewed 35 lists of CRMs, identifying 51 different materials featured on at least one of those lists. This range of materials reflect various economic differences and positions in value chains, as well as distinct perspectives on risk. Risk and security considerations precede the definition of criticality.

At the EU level, these perspectives arise from a series of stakeholder meetings. As the stakeholders involved primarily consist of economic actors, they consolidate a specific view on supply risks that is closely linked to their main interest in commercial activity and capital accumulation. Criticality is then a product of “mundane, routinized security practices”, which are strongly influenced by specific dominant perceptions of risk. This means that while the process of defining criticality is a standardised technical and bureaucratic act, it is not neutral, but depends on the views of particular stakeholders and is therefore subjective.

Power relations determine criticality.

For mining-affected communities, the perception of risk differs significantly. They view land grabbing and environmental degradation as the primary risks associated with specific raw materials. However, in the EU assessment, raw materials are deemed critical primarily because of their economic significance; neither ecological nor human rights issues are integrated into the screening process. This is an expression of power relations; given their various resources, industrial actors enforce their interests, hidden behind technocratic language. Their perspectives manifest themselves in the methodologies and parameters of the criticality assessment, or in successful lobbying campaigns to include specific raw materials in the CRM-List.

Criticality varies over time.

Criticality is not a stable condition but mirrors dominant technological pathways and their embeddedness in the political realm: Lithium is a prime example as it only appeared on the EU’s List in 2020, when lithium-ion batteries were taking off as key component of EVs. Like lithium, specific raw materials only gain significance and value due to changes in the economic, technological, political, cultural, or scientific landscape. The question whether sourcing-countries are trustworthy partners is an essential component in the classification, too. This also depends on the fluid political dynamics. With the global balance of power in flux, Western governments are increasingly wary of over-dependence on countries like China for critical raw materials. Concerns about the use of CRMs as (geo)political instruments in form of trade restrictions resonate with broader security discourses and the EU’s goal of achieving (open) strategic autonomy. These strategies responding to global political dynamics influence the assessment of criticality, and as a result, more than twice as many raw materials than in 2011 are now classified by the EU as critical. The changing socio-technical and the (geo)political context are therefore important determinants of criticality.

The critical dimension of criticality

The concept of criticality should not be seen as neutral but is first and foremost a social construction. This means criticality is actively produced; raw materials become critical through social processes. It is primarily not geology that determines criticality, but a political bureaucratic process that is strongly influenced by power relations. When operationalised, criticality carries material implications. It enhances, with the help of technocratic language and knowledge, the trend to see raw materials simply through the lens of “supply security”, making them not a political but a security issue. And as the EU Commission states, “[t]he CRM list has already helped to incentivise the investment into production of CRMs in the EU and abroad”. The institutional revaluation of raw materials can lead to the expansion of the extractive frontier and amplify social and ecological risks. Criticality, then, runs the danger of overshadowing the negative impacts of mining while foregrounding an instrumental, and economic rationality.