The global nickel market in transformation

Nickel-bearing ores are currently mined in more than 25 countries around the world. Ores are transformed into intermediate products (e.g. nickel mattes), which are then used in different production processes, notably for stainless steel (65% of processed nickel), batteries (17%), and nickel alloys and plating (10%).

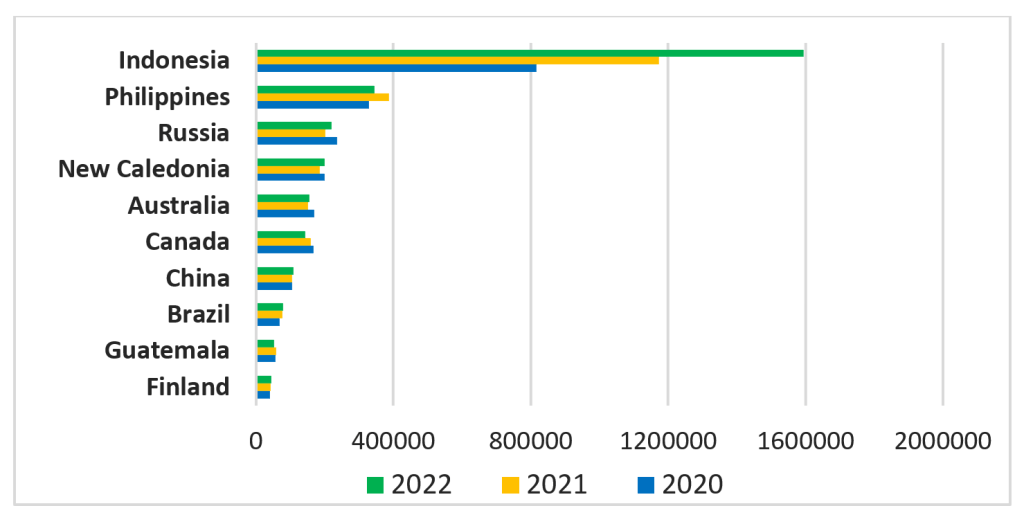

Global demand for nickel is strong and expected to rise until at least 2040, particularly for energy and digital transitions, and a strong growth of EV vehicles, with their batteries requiring ca. 40kg of nickel. Nickel is therefore on the EU list of 34 critical raw materials (CRMs) (EC, 2023). But traditional suppliers of the mineral have changed. By 2022, Indonesia accounted for 49% of the world’s nickel production, having rapidly become dominant, supported by protectionist measures and often backed by Chinese investment (Fig. 1). Its dominance raises concerns about labour, safety and environmental conditions, as indicated in a 2024 Climate Rights International report.

Other producers are finding it hard to compete. In 2024 BHP is shuttering its Nickel West operations in Australia, with analysts now predicting the eventual end of Australian production.

China consumes 60% of global nickel ores, needing to import most of them. Beijing is investing ore processing at home and production and processing in Indonesia, particularly for low-grade lateritic nickel. Chinese co-funding is supporting new innovations in hydrometallurgical smelters. Other beneficiaries of Indonesian production include the French company Eramet, operating at Weda Bay on Halmahera, and now investing in a smelter with its German partner BASF, despite concerns about environmental damage and the respect given to Indigenous communities.

We now focus on New Caledonia-Kanaky (NC-K), with its mine closures in recent months despite being a major world producer for decades. Thousands of workers and its local economy have been affected. Could the Indonesian nickel sector be responsible for the recent withdrawal of two Swiss giants, Glencore and Trafigura, from their respective operations in NC-K?

Local impacts on the nickel sector in New Caledonia

Nickel was discovered in NC-K in 1853, and the first smelter opened in 1910. That is still operated by Société Le Nickel (SLN), part of the French Eramet group. Since the early 2000s, two other processing plants were built: Goro Nickel in the south (operated by the Caledonian-Swiss consortium Prony Resources with Trafigura) and Koniambo in the north (operated by the Caledonian-Swiss consortium SMSP and Glencore). The two Swiss groups, Glencore and Trafigua, have recently withdrawn from New Caledonia-Kanaky citing economic reasons. SLN is also in serious financial difficulties.

Has this resulted from China’s support for a reliable flow of Indonesian nickel? Possibly, but in the Tribune de Genève, Sallier (2024) suggests neither company mastered efficient metallurgical processing at their complex NC-K plants. Trafigura is primarily a commodities trader, while Glencore is a trading, brokerage and mining company. This aside, when the Koniambo plant was under the management of Xstrata (later bought by Glencore in 2012), operating costs were expected to break even if nickel was $8,000 per tonne, and if the plant ran at full capacity. Nickel is still selling for over $15,000 per tonne today despite falling since May 2024, which leaves some potential for profit.

With plant shutdowns combined with major political problems and street violence, the New Caledonian economy is now in a dire state. The nickel sector only contributed 4.1% to New Caledonian GDP in 2017 (it has fluctuated between 3% and 9% over the last ten years), but it accounted for 93.9% of export values in 2019. An ISEE study in 2020 found a quarter of all private-sector employees in New Caledonia-Kanaky were directly or indirectly dependent on the nickel sector, but this may have dropped.

Impacts on Koniambo

Glencore invested over US$9 billion to build and operate the Koniambo project (Fig. 2), but it also has symbolic value to Kanak people because it is majority-owned by SMSP (itself owned by the pro-independence, Kanak-dominated North Province). Mining controlled by Indigenous people is extremely rare at this scale. Koniambo figured in an industrial and urban rebalancing policy dating to the 1988 Matignon Accords, to reduce socio-economic disparities between the north and south of the country where Nouméa and its conurbation is so dominant (67% of the total population live there).

Koniambo’s carbon-powered furnaces have been maintained since Glencore left, as have local jobs for 1,200 people and community subcontractors, with government assistance. But community subcontractors like SAS Vook and SAS Taa Poa only got short-term contracts since February. And from August 31, 2024, the plant entered ‘cold shutdown’. KNS employees were firstly reduced to around 200, and will progressively be reduced to 50 by February 2025. It’s the end of an era. Glencore will finance full closure, if required.

Despite production increasing in 2023 after a spate of earlier technical problems, Koniambo has struggled to find a new operator. In August 2024, three mining companies expressed interest in taking over the 49% stake: a Greek, an Indian and a Chinese group. Discussions are still underway.

Conclusion

With ongoing violence in New Caledonia-Kanaky and continued Indonesian nickel competition, it is unsure if a takeover of production at Koniambo will happen. The future of the other two smelters with reduced or halted production is also uncertain. So, the archipelago has experienced a perfect storm – external competition for its major export, nickel, combined with a serious and very costly breakdown in human security and economic activity. NC-K’s persistent ethnic inequalities and demands for independence for France are not easing, particularly among frustrated young Kanak affected by educational failures and unemployment. They took to the streets from May 2024. France’s Indo-Pacific strategy, which would keep NC-K as French, is deeply unpopular, and viewed as colonial.

To answer our question, all of this has hastened the withdrawal of foreign players in the nickel sector, along with soaring energy prices. Since Koniambo is linked to economic emancipation of NC-K, can it, at least, be supported?