More than half of the resource base of energy transition minerals and at least 54% of energy transition mining is located on or takes place near the lands of Indigenous and peasant peoples. It is crucial that Indigenous rights holders and peoples living on these lands are actively involved in decision-making. As an Indigenous representative and Deputy Chair of the Board of the Sámi Parliament of Sweden, I attended the Beyond Hot Air workshop in Vienna in May 2024 and made the following intervention, adding a critical voice to the ongoing conversation about critical raw materials (CRM) and the European energy transition.

Parliamentary systems or the courts? Justice in decisions on Indigenous people’s lands

The Sámi Parliament of Sweden is concerned about the degree of inequality that exists between Indigenous and non-Indigenous individuals in the Nordic states and beyond. Indigenous peoples have limited respect in the political systems of their respective states. This is a reflection of the ways in which racism permeates western society and underlies structural and institutional discrimination in Europe.

At its inaugural meeting in 2002, the UN Permanent Forum on Indigenous Issues established the need for a report on the status of the world’s Indigenous peoples. Released in 2009, the United Nations Report on the State of the World’s Indigenous Peoples (UN SOWIP) further illustrates that Indigenous peoples are impacted by structural racism globally.

Where parliamentary systems have failed to secure Indigenous rights, juridical systems have done the opposite. Influenced by developments in international law, the supreme courts in three Nordic states ruled in favor of Indigenous peoples: Deatnu (Finland), Fosen (Norway) & Girjás (Sweden). This was groundbreaking!

Sweden lacks data for Indigenous people’s culture and livelihoods, which the OECD described as harmful in the report Linking the Indigenous Sami People with Regional and Rural Development in Sweden. This lack of data must be addressed, as issues facing Sámi people cannot be identified and addressed without statistics.

The Swedish Sámi Parliament lacks the right of veto on mining issues, and we do not disagree with this approach. It is also often forgotten that various Sámi actors do not necessarily have the right to agree to extraction of natural resources either, even if they would want to approve extractive activities. If there is a need for the wellbeing of a nation state, the process of expropriation can be handled in the courts; this is the way forward, as court processes have been more balanced for Indigenous peoples and their organizations, as they have often become targets in highly imbalanced debates in dominant society.

Climate Change, Traditional Livelihoods, and Green Colonialism

The Kimberley Declaration from the summit of the Indigenous Peoples Council on Biocolonialism (IPCB) in 2002, stated the following: “Since 1992 the ecosystems of the earth have been compounding in change. We are in crisis. We are in an accelerating spiral of climate change that will not abide unsustainable greed. Today we reaffirm our relationship to Mother Earth and our responsibility to coming generations to uphold peace, equity and justice. The commitments which were made to Indigenous Peoples in the [UN] Agenda 21, have not been implemented due to the lack of political will.”

The Sámi Parliament is concerned about the unsustainable overuse of the natural resources of Sápmi. Our traditional way of life is highly threatened. Our biological diversity faces collapse in the near future. The “green transition” – as it is described among the European Union member states – is simply continued colonialism.

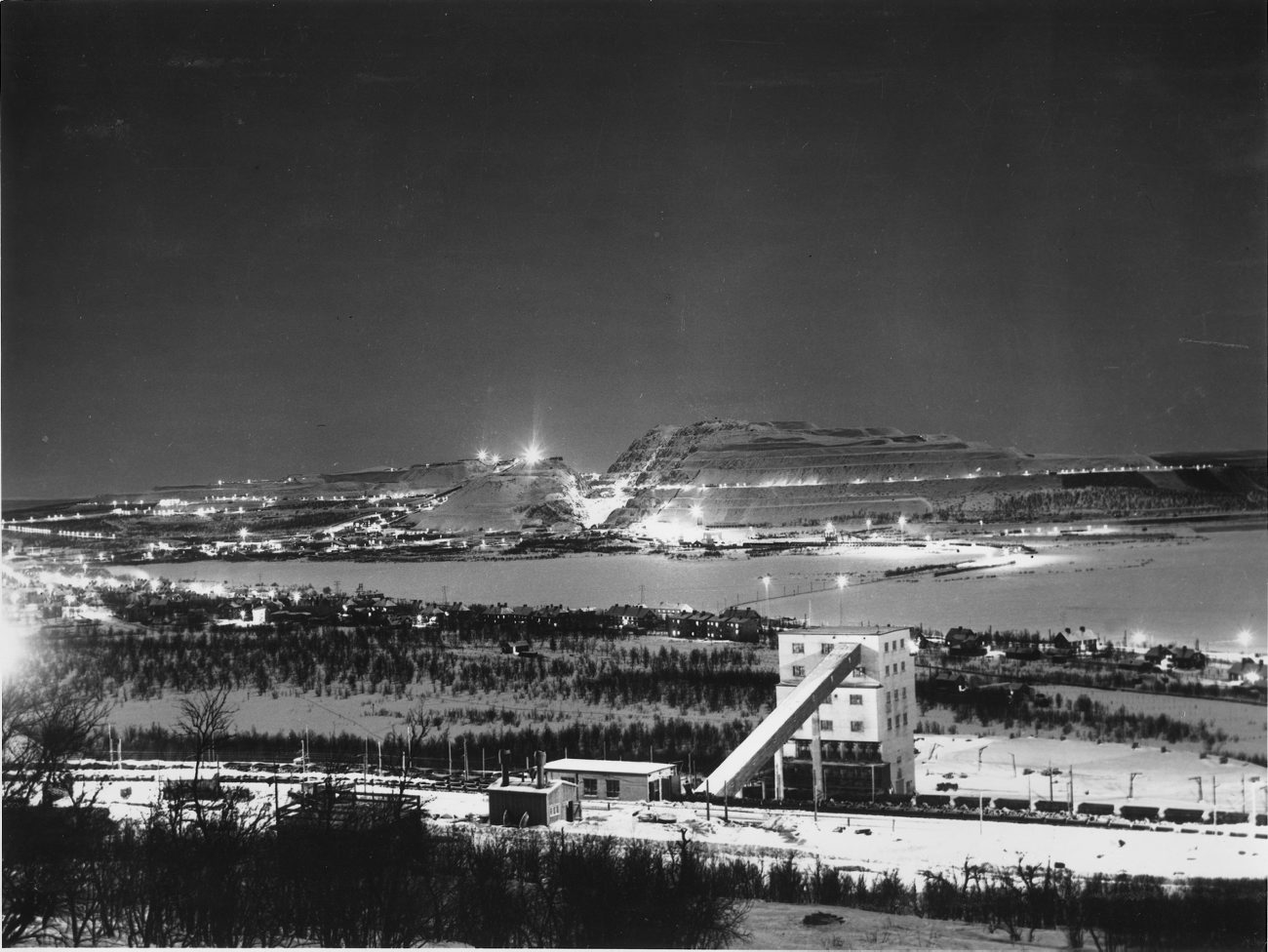

We can observe how the predatory extraction of natural resources in the circumpolar Arctic has created arctic deserts or conditions of desert looking areas. Let me briefly mention three extraction projects:

Alberta Canada’s tar sands extraction is one of the largest fossil fuel projects on earth. It is extremely harmful to both the environment and Indigenous culture. I became well-informed about the project from eyewitness delegates at the 2009 Indigenous Global Summit in Anchorage.

Russia’s Yamal Peninsula’s gas-extraction and other industrial activities in Yamal are harmful for the environment and put pressure on Indigenous livelihoods of Nenets people. However, Nenets cultural resilience has enabled some adaptation for the time being.

Laponia, a UNESCO World and Cultural Heritage site, located in the Kingdom of Sweden, where predatory extraction of natural resources in areas surrounding the area itself, will affect the content of the only world and cultural heritage site in the country. UNESCO is currently investigating if mining permits there will affect the UNESCO status of the Laponia area.

The World Bank, as well as the UN Food and Agriculture Organization, acknowledge on their websites that lndigenous peoples of the world make up 6-7% of the world’s populations, yet occupy 24% of the world’s total area, and in these areas, exist 80% of the remaining biodiversity. Further, if global warming is up to four times greater in the Arctic compared with other parts of the world: What conclusions can be drawn?

The only conclusion to be drawn is that preemptive measures must be four times greater in the Arctic than in any other part of the inhabited world. To put it simply, destroying Indigenous cultures and livelihoods, destroys the remaining biodiversity of the world and the futures of generations to come. Resource extraction plays a defining role in this context.

Today, the Sámi Parliaments of the Nordic states must continue the development of our transnational Sámi community, where we can coexist with our European neighbors on equal terms with our respective parliamentary systems. We must be allowed to continue to live and survive with small-scale activities that provide nutritional food, clean water, and thrive within our cultural heritage.

Our traditional territories are the core of our Indigenous existence, we are the territory and the territory is us.