DECEMBER 11, 2024

By Prakash Kashwan, Brandeis University & Aseem Hasnain, California State University, Fresno

Times Square, the iconic heart of New York City, is renowned for a modern ritual that reminds one of an age-old practice. As the year draws to a close, millions around the globe fix their gaze on a crystal ball, its descent accompanied by a rapturous countdown announcing the arrival of the New Year. Teeming with excited tourists, this hyper-digitized monument to western modernity also tells a more sordid tale. Every shining pixel on those giant plasma screens, billboards, and dazzling façades is fueled by extraction of material, energy, and labor, with grave social and environmental impacts.

Skyscrapers and energy guzzling billboards in metropolitan cities (top image: Times Square, New York City) mask the hazardous labor of the global underclass mining for rare minerals (bottom image: Mining in Kailo, DRC.)

Photo credits – Top image: Times Square, New York City (HDR) by Francisco Diez, via Wikimedia Commons, made available under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License

Bottom image: Mining in Kailo 2 by Julien Harneis, via Wikimedia Commons, made available under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic License

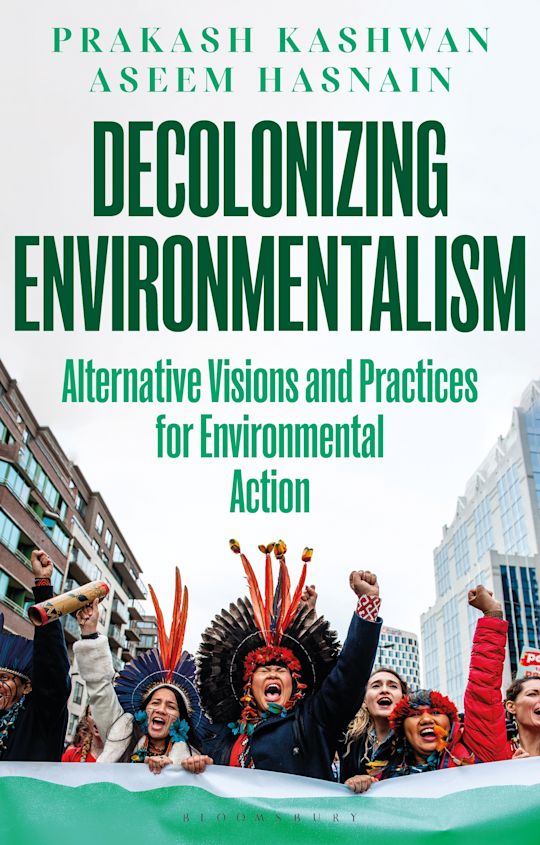

Our new book, Decolonizing Environmentalism: Alternative Visions and Practices for Environmental Action (2024), traces the roots of extractivist models of development to the Eurocentric narratives of progress and development, which cater to the consumerism of a small section of humanity. The enormous amounts of energy needed to power mega cities and tourist destinations like Times Square, Atlantic City, or Las Vegas, leave deep environmental and social footprints in areas that host mines and fossil fuel wells, refineries, and pipelines. In most cases, these are Indigenous territories and neighborhoods composed predominantly of racial minorities, or other socially and politically marginalized groups. Critical minerals for LEDs and plasma screens come from the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC), Mongolia, China, Latin America, and Southeast Asia, where mining operations displace Indigenous and local communities. Social scientists refer to such processes as extractivism – extraction of minerals, materials, and energy that impoverishes local people to provide for the needs of affluent people in Western societies.

Extractivism invariably subjugates and demeans both humans and nature. In the words of American historian, sociologist, and philosopher of technology, Lewis Mumford, “faceless pairs of hands and unseen laboring backs descend into the dark, inhuman hell of tunnels to strip away the organs of nature.” The juxtaposition of the excesses of western affluence vis-à-vis the exploitation of humans and nature should prompt a deeper introspection about Western modernity.

In Decolonizing Environmentalism, we argue that the coinciding crises of extreme inequality, environmental degradation, and climate crisis are rooted in European modernity, in more than one way. One, extractivism is a symptom of the foundational values of European modernity, which yearns for endless material growth and development, even if it requires violent control of nature and marginalized communities. Two, European modernity glorifies individualism and consumption as fountains of human wellbeing. This outdated thinking has led to the dominance of market-based environmentalism in the West, with an assumption that green consumerism would be the main plank for addressing the environmental and climate crises. The evidence that we synthesize in the book shows that an obsession with market-based environmentalism has prevented rich nations from reflecting on and addressing the global consequences of luxury consumption.

The third major blind spot of European modernity is an infinite faith in the power of scientific and technological advancement. It obscures the evidence that European science has been a colonial pursuit that privileged the interests of the West. This history notwithstanding, dominant narratives thrive on the arrogance of technological solutions to the climate crisis, for example untested geoengineering solutions such as Solar Radiation Management and Carbon Dioxide Removal. Decolonizing Environmentalism demonstrates how such ‘risk-risk tradeoffs’ (to employ Western jargon) in planetary-scale technological solutions are likely to produce a redistribution of the risks along historical patterns of global inequalities, especially affecting the most marginalized communities in the Global South.

Fourth, and most importantly, the emphasis on individual action, market-based solutions, and the hubris of technocratic thinking has detracted from the urgent need for collective public action to stem environmental destruction and climate crisis. The failures of affluent countries – responsible for nearly three-quarters of greenhouse gases responsible for the climate crisis – is symptomatic of a collective failure to reimagine a society beyond the self-destructing cycles of boom-and-bust capitalism, outsourcing, and corporate capture of regulatory apparatuses.

Going beyond a deeply critical scrutiny of the status quo, Decolonizing Environmentalism also offers nuanced pathways towards an egalitarian, regenerative and solidaristic environmentalism. We engage with the trajectories of youth climate movements, such as Fossil Fuel Divestment, and Fridays for Futures that have called out Western leaders on these failures and have demanded that governments respond to the climate crisis. While celebrating the accomplishments of youth climate movements, we also draw insights and lessons from the approaches and strategies these movements developed to question the moral and cultural legitimacy that the fossil fuel industry enjoys in the status quo. This applies even more strongly to our approach to learning from Indigenous environmentalism.

Sustained pushbacks from Indigenous scholars and activists have ensured that the rights of Indigenous and frontline communities are invoked routinely in policy debates. Yet, the recognition of Indigenous Peoples and environmental justice communities has been tokenized. Indigenous wisdom is often used as a metaphor for wishful thinking among Western environmentalists about a world that could be. Barring a few cases, avowed commitments to rights-based and “inclusive” environmental and climate action have been deployed as rhetoric, even as multinational mining conglomerates and fossil fuel companies continue to violate Indigenous Peoples’ rights. Decolonizing Environmentalism confronts such trivialization of rights. We draw lessons from the praxis of Indigenous environmentalism, which are based on ecologically smart material practices. We show that situating Indigenous environmental praxis contextually is crucial for appreciating its broader contribution to the conservation of biodiversity, soil health, and ecological resilience within Indigenous territories.

More broadly, we scrutinize the stereotypical compartmentalization of social and environmental movements to integrate lessons from a diverse set of movements to outline new visions of a regenerative and emancipatory decolonial environmentalism. We build on insights from Black Feminism, Black Lives Matter, Ecofeminism, and La Via Campesina’s movement for food sovereignty. Learning from these movements and anti-colonial scholars and activists, we provide a pathway for building solidarities and visions for a just and thriving world. Such an approach leads us to argue that decolonizing environmentalism is necessary, not just for the sake of formerly colonized countries or Indigenous Nations subjected to settler colonialism, but also for imagining a truly global environmental movement that is just, inclusive, and effective in the long run.

You can read more about Decolonizing Environmentalism (Bloomsbury 2024) here.

Contact: Prakash Kashwan – pkashwan@brandeis.edu

Contribution: Ellen Marie Jensen (Austrian Polar Research Institute APRI), Emma Wilson (ECW Energy)