MARCH 6, 2025

By Arthur Mason, Department of Geography and Social Anthropology, Norwegian University of Science and Technology, Gisa Weszkalnys, Department of Anthropology, London School of Economics, Synnøve K. Bendixsen, Department of Social Anthropology, University of Bergen

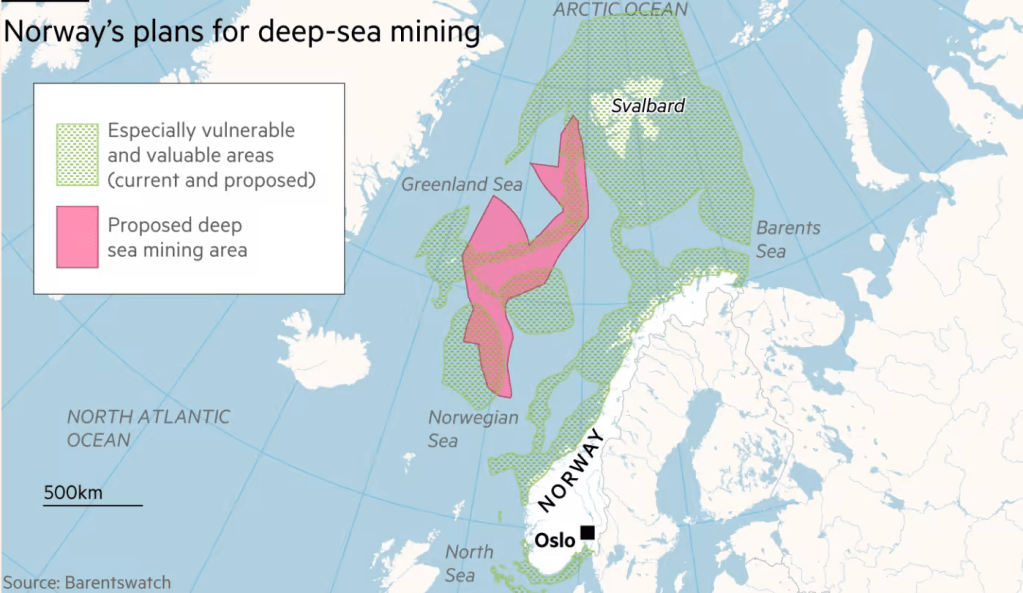

In June 2024, the government of Norway moved to open 281,000 square-kilometers of the ocean for Deep Sea Mining (DSM) including areas near the Svalbard archipelago in the surrounding Greenland Sea. The intention to mine manganese crusts for manganese and iron and smaller amounts of metals such as cobalt, nickel, copper, lithium, scandium and other rare earth elements recognizes the Norwegian government’s aspiration to capture rents from emerging green transitions. But doing so is also heightening concern among environmentalists and scientists about the rapidity of informational processes in determining how commercial seabed mining will affect marine environments as well as nonhuman and human inhabitants of Svalbard (e.g., cod spawning areas, cold coral reefs). While the effects of seabed mining are little understood, abundant scientific evidence confirms the long-term sublethal cascading effects of ocean floor mining for land and marine ecosystems as well as for local ways of life.

‘Making Use of Arctic Science’ Workshop

A year prior to the Norwegian government’s decision to launch a licensing round for DSM, in May 2023, we participated in a weeklong workshop in the town of Longyearbyen in the Svalbard archipelago to consider the rapidity of environmental change from global warming, ocean acidification, pollutants from toxic chemicals as well as emerging concerns related to DSM. One of us, Arthur Mason, convened the workshop – co-sponsored by UC Berkeley’s Peder Sather Center for Advanced Study, the Norwegian strategic initiative NTNU Oceans, and The University Centre in Svalbard (UNIS) – bringing together people with expertise working at the intersection of physical sciences, ethics, policy, anthropology, and the arts, to explore sustainability under the title Making Use of Arctic Science.

The workshop included three days of interdisciplinary presentations and discussion as well as a public debate held at UNIS in Longyearbyen where town residents, members of the artist collective Artica Svalbard, students, and faculty, gathered to discuss whether the Svalbard archipelago should – again – become a hotspot for the exploitation of natural resources or whether instead its fragile environment should be protected more strictly in the coming years.

Svalbard Archipelago in Transition

The Svalbard archipelago is a locally administered area managed by the constitutional monarchy of Norway and has long been a resource base for whaling, hunting, and coal mining but more recently an important focus of nature conservation as well as location for cultural heritage, international science, and tourism. The archipelago’s sublime landscapes of rugged coastlines, fjords, and mountainous terrain give the impression of a wilderness untrammeled by modern industry while inspiring passion for safeguarding a sense of pristine nature. A century of coal mining is coming to an end, raising concerns for residents attending our public event. Miners and other inhabitants discussed the archipelago’s energy (in)dependence, the need to retain the community’s closely knit social relations, and other possibilities for using the landscape (e.g., eco-tourism). The Norwegian government increasingly portrays Svalbard as a location for climate science as symbolized by the establishment of UNIS in 1993 and an international research station at Ny-Ålesund, formerly a coal mining settlement.

The Concern of Development

In Longyearbyen, our discussions at UNIS pivoted around three concerns related to commercial DSM: First, the advice of environmentalist groups such as WWF is to slow down the process of exploration over fears of a renewed and still largely unregulated race for extractive industries in vulnerable Arctic waters. Second, among the natural scientists, steps toward mining the sea for metals pose an inherent contradiction when there are calls by government for more protection of the fragile marine environment against biodiversity loss leading to species extinction.

Third, the three of us, as anthropologists, observed that the arguments at work among experts often demand ecological vulnerabilities be expressed as probabilities of harm, and these are developed by actors who may or may not be responsible to the communities and environments affected by the risks to Svalbard. At the same time, we were impressed by the heartfelt concerns of scientists, several of whom are residents of Svalbard, and whose distinctions are not drawn from traditional forms of science as purified knowledge but based on the first-hand social values and epistemologies of being-there. Moreover, the scientists in our midst pointed out that laboratory studies do not offer sufficient insight into the effects that mining will have on these marine environments, not only because they are highly complex, inaccessible and under-studied, but because calculations based on an idealized notion of probable harm use a naïve model based on global assessments of risk.

Fast-Tracking Development

One point of consensus was that public and policy debate surrounding DSM must be restructured to adequately involve a wider register of participants, arguments, and emotions in conversations about environmental safeguarding. At present, DSM is being fast-tracked through objections based on “knowledge gaps” around environmental baselines and the risks of industrial activity. These topics privilege the interests of elites such as government officials who assume that mining development and associated exploitation and harm will go ahead, albeit within defined ecological limits. This gives the impression that impacts are manageable. The tone of debate is thus out of step with sustainability goals that prompt actors to reflect on the depletion of Earth’s resources and habitats and the possibilities for degrowth and alternative understandings of quality of life: therefore, avoiding DSM if possible. Moreover, elevating voices that speak in the name of profit short-circuits a democratic sense of deliberation and oversight, while epitomizing fundamental forms of collusion.

Discussions at the Making Use of Arctic Science workshop suggest a reconfiguration of DSM around Svalbard as a complex and heterogenous environmental problem that will require more integrated methodologies and institutional solutions. In debating a way forward, social sciences cannot be reduced to facilitating stakeholder participation or making science and industry responsive to societal demands. The process should involve advocating slowing the policy process of development itself and to consider alternatives to development.

Rebuilding Value through Safeguarding

Our own contributions suggested a potential for anthropological investigations. AM, for example, highlighted the ruinous effects of Abstractive Industries meaning those that conceptually enable material extractive industries to create exchange value. GW reflected on speculations about resource availability that leave social actors suspended between expectation and apprehension: will they gain or lose in some way from mining going ahead? SB stressed acknowledging the diverse ways knowledge is co-produced within a framework of endangerment sensibility (concerns about extinction in deep seas) that are influenced by moral and political values. In this way, and drawing from our combined ethnographies of late industrial themes such as vulnerability and financialization, the three of us prompted participants to reflect on the safeguarding of the Earth and the possibilities for rebuilding value through better safeguarding mechanisms that include more caution over DSM.

In practical terms, together with other participants, we discussed how applying these perspectives can challenge a dominant framing of DSM as a purely techno-scientific exercise accessing materials of great value to the green transition, and reveal the need for more expansive, imaginative rethinking beyond nature as an infinite resource. This should involve Arctic people and cultures much more in our collective relationship with the deep sea.

Contact: Arthur Mason – arthur.l.mason@ntnu.no

Contribution: Simon Batterbury (Uni Melbourne & Uni Lancaster), Frank Melcher (Montanuni Leoben), Gerti Saxinger (Uni Vienna & Austrian Polar Research Institute APRI)